In past months, concerns have been raised across the country about the detention of children and young people in police cells. Detention in these environments often exposes young people – who may be primary-school aged, and many of whom have complex disability needs – to adult offenders, and conditions that are harmful and potentially traumatic for children.

In past months, concerns have been raised across the country about the detention of children and young people in police cells. Detention in these environments often exposes young people – who may be primary-school aged, and many of whom have complex disability needs – to adult offenders, and conditions that are harmful and potentially traumatic for children.

This is not just an issue occurring in other states and territories – it is happening in South Australia. As stated by Guardian for Children and Young People and Training Centre Visitor (TCV), Shona Reid:

“We need to pay extra care and attention to how our services and communities respond to children and young people, due to their developing needs. We can’t treat them or build systems in the same way as we would for a grown adult.

“The United Nations has clearly articulated that detaining children and young people in adult facilities is a human rights violation. Yet we are still doing it.”

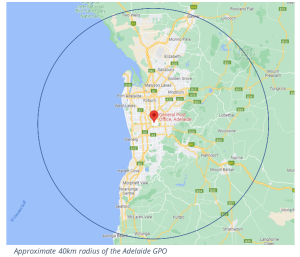

Earlier this year, the Hon Robert Simms MLC moved a motion to disallow South Australia’s youth justice regulations which permit children and young people arrested outside a 40km radius of the Adelaide CBD to be detained in police cells until it is ‘reasonably practicable’ to transfer them to South Australia’s only youth detention facility, in Adelaide.

The Legislative Council voted on the motion earlier this week, and it did not pass. This means children and young people arrested outside a 40km radius of the Adelaide CBD can continue to be held in police cells.

To help shine a light on this issue, we’ve broken down some of the background, and what this means for children and young people in South Australia.

When can children and young people be held in police cells?

When a child or young person is arrested, they may be transported to police facilities for interviews or while other investigations are underway. If they are charged with a crime, then they may be released on bail, or detained on remand for a limited period until they can be brought before a court.

For children and young people who are not released, the places they can legally be detained depends on where they were arrested.

While young people arrested within 40km of the Adelaide General Post Office can only be legally detained at the Kurlana Tapa Youth Justice Centre (the Youth Justice Centre), there is an exception that allows those arrested outside that radius to be detained in police cells if it is not ‘reasonably practicable’ to transport them to the Youth Justice Centre.

“I understand that, in most circumstances, young people arrested outside metropolitan Adelaide are transported to the Youth Justice Centre as soon as possible. But it’s worrying that there isn’t a limit or clear legislative guidance on how long they can be held in police cells,” Shona said.

“When we talk about police cells, we need to be clear that we are often talking about cement beds, cement walls, stainless steel toilets, caged doors and in full view of adult offenders.”

“It has been reported to my office through documentation requests that, in 2020-21, a young person was in fact held in police cells for 68 hours and 37 minutes.”

How often are children and young people held in police cells?

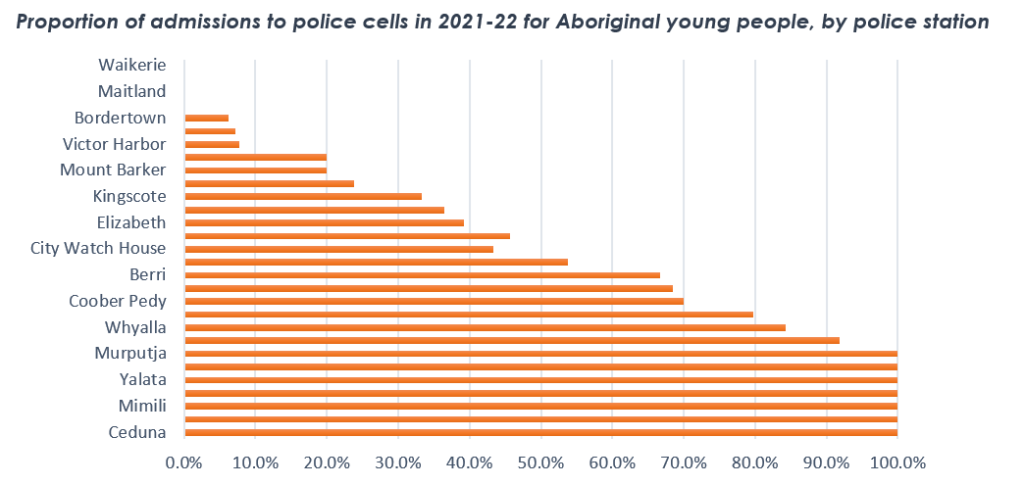

In her recent Annual Report as the Training Centre Visitor, Shona Reid published the following data about the number of times that children and young people were detained in adult facilities in 2021-22:

- 1,097 individual young people were taken into police custody across a total of 2,819 detentions.

- Nearly one in four (24.3%) admissions to police custody were for children under the age of 14 years.

- In some regional and remote areas, up to 100% of admissions to police custody were for Aboriginal young people.

- 15 young people were held in police custody for more than 24 hours. One was in the Adelaide metropolitan areas, with the remaining 14 in regional and remote areas.

- For those young people detained for longer than 24 hours, 80.0% were Aboriginal and 13.3% were under the age of 14 years.

What are the concerns with holding children and young people in police cells?

For years, the Guardian/TCV and her predecessor have raised concerns with the South Australian government about the conditions for children and young people held in police cells. Our office has heard direct accounts from young people of rough treatment and verbal abuse, being subjected to strip searches, having frightening interactions with adult prisoners and detention conditions that they found humiliating, degrading and traumatising.

Young people have described to the Guardian/TCV’s advocates being held for multiple days in regional police facilities over weekends. This can be a particular issue over long weekends, such as Easter or Christmas public holidays.

Concerningly, these issues arise not only in regional and remote areas, but also in the Adelaide City Watchhouse and other metropolitan police stations. Despite legislative requirements that they be detained at the Youth Justice Centre once bail is denied, children and young people have frequently described being held overnight in metropolitan facilities. This appears to be consistent with relevant SAPOL and Department for Human Services policies, and operational records such as shift logs for the Youth Justice Centre. Relevant records have also revealed circumstances where children self-harmed during these periods of detention in metropolitan police cells, prior to admission to the Youth Justice Centre.

In light of such issues, then Guardian and TCV, Penny Wright, recommended in June 2022 that:

- the South Australian government undertake an urgent review of the practice of holding children and young people in police facilities to ensure that any such detention only occur in accordance with strict compliance with child safe principles

- the TCV be granted statutory oversight responsibilities for police facilities that function as a place of detention for children and young people.

Nearly eighteen months later, there is still no independent child-focused oversight of police facilities, and no such review has occurred. Despite multiple requests, the South Australian government has not formally responded to whether these recommendations have been accepted – and, if not, why not.

“Where government will not provide the legislative authority and resourcing for child-focused oversight of police facilities, that makes me worried about what’s happening in those places,” Shona said.

“I am forced to ask the question: what do they have to hide?”

How has the government responded to the Guardian/TCV’s advocacy?

Earlier this year, the Guardian/TCV wrote to the Minister for Police, Emergency Services and Correctional Services to request an update on any actions taken in response to the above recommendations.

The Minister’s reply correspondence, dated 30 June 2023, did not formally respond to the Guardian/TCV’s recommendations, or provide a rationale for not implementing them. However, the Minister did provide the following information about the detention of children in police facilities:

“Typically, if a child or young person is refused police bail, efforts are made to have them transferred to court or [the Youth Justice Centre] as soon as practical. The timeframes involved are often dependent on the capacity of the agency receiving custody of the detainee to accept them, but are considerably lower than those seen for adult prisoners within police cells. Interagency collaboration is being undertaken to further reduce the amount of time spent in police cells by children and young people.

“SAPOL’s ability to comply with s 15(1) of the [Young Offenders Act 1993] has been impacted by the decision to close the Adelaide Youth Court cells.” (emphasis added)

Concerningly, no further information was provided about the nature of the impact on SAPOL’s ability to comply with the Young Offenders Act 1993. However, it is significant that the relevant provision (s 15(1)) prevents children and young people arrested in metropolitan Adelaide from being detained in police cells.

In addition, the Minister’s correspondence highlighted that ‘Official Visitors’ have the power to inspect SAPOL facilities. These visitors are assigned responsibility for adult correctional facilities, as part of South Australia’s current (and problematic) OPCAT National Preventive Mechanism arrangements. With great respect to the work of the Official Visitors, the Training Centre Visitor maintains that specific child focus and expertise is required to oversight the suitability of detention facilities for children and young people – both on an individual and systemic level. The importance of this focus is apparent in the annual reports of the Official Visitors, which were tabled in Parliament this week. While 15 police facilities were inspected throughout the year, these reports do not mention any circumstances specific to the detention of children and young people.

The case for specialised child-focused oversight expertise is well established in international best practice guidance and advocacy. As highlighted in a report by the Association for Prevention of Torture, monitoring places where children are deprived of their liberty requires a high degree of sensitivity and professional knowledge across a number of fields including social work, child rights, child psychology and psychiatry.

“I hold the firm opinion, as did my predecessors, that my Training Centre Visitor mandate should be extended to the oversight police cells for children and young people,” Shona said.

“The voices of children and young people about their experiences in police facilities are loud and clear. My office has the youth-centred systems in place, and the connectivity to the child protection and youth detention sectors, to provide independent oversight and advocacy functions. I simply don’t understand why government is not willing to act on this.”

What does this mean for children and young people in regional and remote areas?

With the motion made by the Hon Robert Simms MLC in the Legislative Council not passed, the result is that relevant regulations will stay in force. This means that children and young people arrested outside a 40km radius of the Adelaide CBD:

- can continue to be held in police cells

- for an indefinite time period

- without access to child focused advocacy and oversight.

In advising that the government would not support the motion, the Attorney General noted in Parliament the importance of allowing children and young people to be detained in police facilities in regional and remote areas, due to the significant travel required to transport children and young people to Adelaide.

This office shares the Attorney General’s concerns about youth justice responses that involve unnecessarily transporting children and young people in regional and remote areas to Adelaide. In her recent annual report, the Training Centre Visitor noted that she witnessed children from regional and remote areas who were transported to the Youth Justice Centre, following lengthy remand orders made by Country Magistrates. Often, at their next court hearing, these young people were bailed and returned to their communities. This transport can be distressing, and may introduce unnecessary risks for young people’s health and safety.

This issue requires investment in adequate diversion opportunities and appropriate infrastructure and facilities. Not having these in place does not excuse the ongoing detention of children and young people in adult police facilities. As explained by Shona:

“I have recently visited police cells in regional areas, and I can personally attest that these are not suitable places to hold children and young people,” Shona said.

“I do not doubt that local community police try their best to keep children and young people safe in these environments. What I am calling out is the State’s unwillingness to provide facilities that are amenable to children and young people, that meets the immediate need without stripping them of their human and developmental rights.”

Where can you find more information?

The Guardian/TCV has engaged in significant advocacy efforts regarding these issues, with a number of publications detailing the circumstances of children and young people detained in police cells in South Australia. This includes the following:

- Training Centre Visitor’s 2022-23 Annual Report (2023)

- Training Centre Visitor’s 2021-22 Annual Report (2022)

- Final Report of the South Australian Dual Involved Project (2022)

- Call to governments to give OPCAT powers to oversight bodies (2022)

- Alarming numbers of young people being held in adult police cells (2021)

For further information and enquiries, please contact Alicia Smith, Senior Policy Officer at gcyp@gcyp.sa.gov.au or (08) 8226 8570.