Earlier this month, Shona published her first annual report as the Child and Young Person’s Visitor.

It was a big 12 months for the Visiting Program – after the government announced funding, Shona was appointed to the Visitor role in mid-2022 and work began on recruiting a team of advocates and establishing the program.

Visits were up and running from December 2022 and advocates aimed to visit as many of the approximately 700 young people in residential care as they could over the following six months. With funding for only three advocates, they couldn’t see everyone – but they did make it out to visit 91 young people, living in 30 separate residential care houses.

“Establishing the new Visitor Program for children and young people in residential care has been a privilege,” Shona said.

“I acknowledge the important and integral role of those who are charged with the responsibility of caring for children and young people in residential care houses. Most importantly, I must acknowledge the children and young people who so openly and willingly shared their lives and perspectives with me. I am a ‘teller’ of their stories; they are the experts about living in residential care.”

Houses or homes?

Houses or homes?

One of the big things that young people raised through the year was the lack of ‘homeliness’ in houses, with only one in four describing their house as a ‘home’.

Given there is a workforce that supports children and young people living in residential care, it is important to acknowledge that residential care houses are also workplaces. It is a complicating factor for a house that should be suited to raising children to also be required to meet workplace health and safety standards. One of the unintended consequences is that children are growing and developing in an environment that is geared towards workforce compliance.

Experiencing this lack of ‘home’ is compounded by the level of placement instability in residential care. During visits, young people often reported the number of ‘homes’ they had lived in over their care journey – it is important to acknowledge that the young people are actually counting how many times they move or are placed in different houses.

Young people also spoke about ‘push’ and ‘pull’ factors which led to ‘running away’ from the house or ‘self-placing’ – including to see loved ones, siblings and friends. We also hear about how young people sometimes feel unsafe in their house because of living with people who they don’t know very well, don’t normally share a living space with or might have had recent peer-to-peer conflict with. Sometimes they leave their house because they need a break from this.

Reflecting on these experiences that young people raised during the year, Shona said:

“We know that it is preferable for children and young people to grow up in a family environment, and even better within their own family networks.”

There is, however, a need in specific circumstances for the using residential care settings. Regardless of those reasons, we should do all we can to ensure that these places are as home-like, caring and supportive as possible.”

Transition from care

Another key theme that arose during our visits was the degree of support for young people in residential care in the lead-up to their 18th birthday.

In the wider community, an 18th birthday is generally a time to celebrate, and focus on further education or employment. A sense of opportunity can exist in residential care too, with some young people expressing relief at the end of their time in care, and that they have been in that situation “long enough”.

But a common concern for those approaching 18 was the lack of secure housing and being ‘set up for their future’. In the wider community young people may remain at their childhood home until they have the means or desire to move out. This is not feasible in the strained residential care sector, where there is constant demand for beds, and regulations about the presence of ‘adults’ in the house. Some young people did tell Visiting Advocates that they had permission to remain in their house for three months after turning 18, but this was not standard. Even when placements were extended, some young people expressed frustration at having to remain in a living environment they don’t consider home, for lack of more appropriate alternatives.

But a common concern for those approaching 18 was the lack of secure housing and being ‘set up for their future’. In the wider community young people may remain at their childhood home until they have the means or desire to move out. This is not feasible in the strained residential care sector, where there is constant demand for beds, and regulations about the presence of ‘adults’ in the house. Some young people did tell Visiting Advocates that they had permission to remain in their house for three months after turning 18, but this was not standard. Even when placements were extended, some young people expressed frustration at having to remain in a living environment they don’t consider home, for lack of more appropriate alternatives.

Not only does a young person exiting care have to transition to full independence, they also must say goodbye to who and what they have known, often without connections to the wider community they will enter. Case workers, carers, some medical and mental health supports, and house mates are all still governed by DCP policies and procedures potentially prohibiting or limiting ongoing contact.

“Young people leaving residential care often have to set up a new life almost instantly, which is not an expectation of young people in the wider community,” Shona said.

“I recognise there may be efforts in place to support them – but in reality this is limited by the capacity of the system to support it. We should be questioning if we are really setting these young people up for success into adult life.”

‘Pay particular attention to’

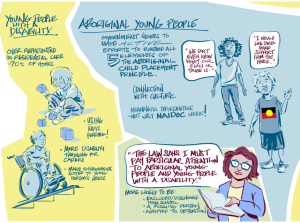

The CYP Visitor has a legislative responsibility to pay particular attention to the circumstances and needs of Aboriginal young people and those with a disability (including mental health related disability needs).

The CYP Visitor has a legislative responsibility to pay particular attention to the circumstances and needs of Aboriginal young people and those with a disability (including mental health related disability needs).

One in three young people visited were Aboriginal, with the same proportion having a disability. Concerningly, information provided by DCP and NGOs indicated that Aboriginal young people and those with a disability were more likely to be:

- excluded or disengaged from school

- reported as a missing person

- admitted to youth detention.

Matters raised by young people and observed by visiting advocates included:

- low cultural support for Aboriginal young people in houses, with limited opportunities to have contact with family and community and young people expressing a desire for more information about their cultural and family background, and better support to engage in meaningful expressions of their culture.

- particular impacts of placement instability and inconsistent care teams for young people with disability, including how these issues affect the suitability of the physical environment for meeting disability-related needs, and carers’ understanding and responses to supporting young people’s needs.

What’s next?

The CYP Visiting program is funded for the next three years, and Visiting Advocates are continuing to visit as many young people in residential care as possible for 2023-24. Talking about the future of the program and its focus for this financial year, Shona told us:

“We will, as always, do our best to provide robust and comprehensive advocacy and oversight for children and young people in residential care facilities. But the extent is very much determined by the resourcing made available to us. I am mindful that my mandated oversight is legislated on an ongoing basis, but the resourcing for the mandate is for only another 3 years.

“If we are truly serious about keeping an eye on how well the system is serving vulnerable children and young people in residential care – then we need to get serious about how we enable this to happen.”

The full report is on our website, with a visual summary also available.