Content warning: This post contains information about experiences in youth detention that may be distressing to some readers, including about self-harm and violence against children. If you experience distress, support is available from the following services:

Kids Help Line on 1800 551 800

Lifeline on 13 11 14.

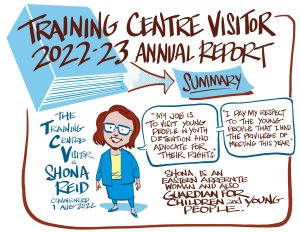

Many of you will have seen or heard Shona Reid in the media this week, after three of her separate Annual Reports were tabled in Parliament. Today’s blog looks at the one that has drawn the most attention: the Training Centre Visitor 2022-23 Annual Report.

As well as more general reporting on her activities, the report highlights Shona’s key observations about the operational philosophy and functioning of youth detention in South Australia.

The report finds that, far from achieving youth detention’s primary purpose – to create a rehabilitative environment for young people where they can get intensive help for their needs – it is more often a scary and lonely place.

In 2022-23, the TCV and her office took a deep dive into exploring perspectives of young people, youth detention data and operational Centre records, across matters such as:

Centre records, across matters such as:

- Isolation, lockdowns and segregation

- Limited access to education and rehabilitative programs

- Significant gaps in trauma-informed responses to mental health needs and self-harming.

The report identified widespread use of practices which can severely undermine trauma recovery, and a critical lack of transparency and accountability in record keeping and reporting – which meant that, even with considerable resourcing and efforts directed towards the task, the TCV was still not able to uncover the full extent of young people’s experiences. Concerningly, this means that the people within government who have responsibility for their care and wellbeing also cannot answer these same questions.

Key statistics:

Key statistics:

- Nearly three in four ambulance attendances over the financial year were responding to young people self-harming

- Two in five individuals involved in incidents throughout the year self-harmed or expressed self-harm ideation during their admission

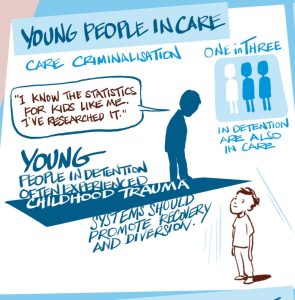

- Aboriginal young people, young people with a disability, and young people in care are all seriously overrepresented in the Centre. All experienced a greater likelihood of having force used against them, and higher rates of self-harm

- At times, over 90% of young people housed in the segregation unit (known as the Protective Actions Unit) were those with disability – including autism, intellectual disability and psychiatric condition

- 39 young people under the age of 14 were admitted to the Centre – two were 10 years old

- One in three incidents for children 14 years and under resulted in the child being restrained to the ground in the ‘prone position’ – a potentially dangerous restraint that has been linked to deaths in custody

- Girls and young women also faced disproportionate use of the prone restraint – two in three girls or young women involved in incidents experienced this restraint, compared to two in five boys or young men.

In the TCV’s office, we always keep at the front of our minds that these statistics reflect the experiences of individual young people – with their own histories, dreams, nicknames and hobbies. For over a third of young people in the Centre on any given day, these stories are interwoven with the TCV’s other mandates as Guardian and Child and Young Person Visitor. Shona’s 2022-23 Annual Report as the CYP Visitor was also tabled this week, providing insight into the residential care system, and what the lives of many of these young people are like outside the Centre’s walls). This report will feature in our next blog.

In the TCV’s office, we always keep at the front of our minds that these statistics reflect the experiences of individual young people – with their own histories, dreams, nicknames and hobbies. For over a third of young people in the Centre on any given day, these stories are interwoven with the TCV’s other mandates as Guardian and Child and Young Person Visitor. Shona’s 2022-23 Annual Report as the CYP Visitor was also tabled this week, providing insight into the residential care system, and what the lives of many of these young people are like outside the Centre’s walls). This report will feature in our next blog.

Of course, those individual stories cannot all be conveyed in one report. In Shona’s words:

“Every one of those children was sent to the Centre because at some point in their young lives, something went wrong. On average, 90% of young people detained in the reporting period were on remand and had not yet been found guilty of their charges.

We must remember that the Centre is meant to be the place to help them, but in its current form I am forced to question whether it can do so. This question is not intended to be dismissive of staff and services. It is about whether the model of care and system of control enables opportunities for healing, recovery and rehabilitation.

I highlight my respect for the many talented and committed people who work daily with and for these young people. They often bear the brunt of a mismatch between wanting to help and assist with rehabilitation and an inflexible operational model that focuses on containment.”

When asked what she hopes will be achieved by publishing her report, Shona told us:

“The South Australian community and our government must not look away from these difficult stories and confronting experiences, but instead face the ongoing and emerging concerns at the centre unflinchingly. Hopefully, my scrutiny will contribute to building a culture where we openly question and seek to improve the Centre’s capacity to actually rehabilitate young people. We must hold the hardest parts of this narrative in our hearts, remembering the young humans who too often get lost among the statistics.”

You can read the full report on our website, or a visual summary for a shorter read. You might also want to look at our In the News page for recent media coverage of the report.