By Guardian Penny Wright

30 years ago, world leaders made a promise to all children. It was a promise that stated that children around the world will not be discriminated against, the decisions that affect them will be in their best interests and they will be provided with opportunities to develop and reach their full potential.

This promise is known as the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC).

For the first time, the UNCRC set out 54 rights for all children, and described how adults and governments should work together to ensure these rights are made available to them. This commitment from world leaders changed the way children were viewed and treated. It gave young people a voice and established that they have basic fundamental rights to survival, development, safety, education, to know or have a relationship with their parents and to express their opinion and be listened to.

This is the most widely ratified international human rights treaty in history. Since it was adopted in 1989, 195 countries have signed up. Only two are yet to ratify: South Sudan and the United States.

Since then, the South Australian parliament has established additional rights for children and young people who are in care, away from their parents, and in detention, locked up in the Adelaide Youth Training Centre. These are the children and young people who fall under my mandate as Guardian and Training Centre Visitor.

Unable to be with their parents, these South Australian citizens have special rights above and beyond the rights outlined in the UNCRC. But thirty years on, what does this all mean for them?

Today, in South Australia we are seriously failing many of the children and young people who need our help the most. The world made a promise but 30 years later children continue to be separated from their family and culture, their identity fractured, moved from placement to placement with little say over the conditions of their lives and excluded from school or locked up from as young as ten for behaviour that is a symptom of their own trauma, neglect, abuse and loss. Many of these young people have undiagnosed disabilities or trauma-related conditions which go untreated. More than a quarter become entrapped in both the child protection and the youth justice system.

Last month, the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child called for Australia to raise the minimum age of criminal responsibility.

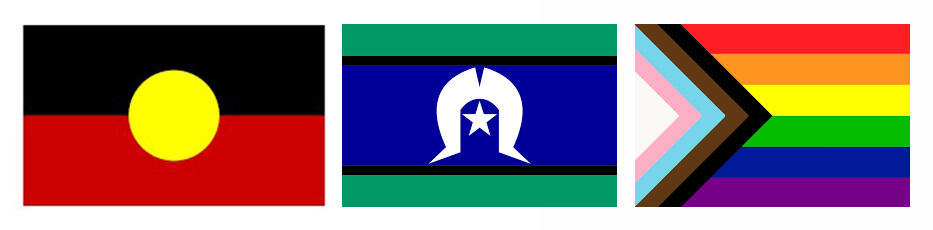

The Committee critiqued Australia’s child protection systems and its excessive reliance on police and the youth justice system when dealing with children’s behavioural problems, rather than providing the appropriate therapeutic services or intervention. It also highlighted that Aboriginal children and young people continue to be over-represented in both the child protection and youth justice systems.

In September of this year, a 12-year-old Arrernte/Garrwa boy, Dujuan, travelled to Geneva and became one of the youngest people ever to give a speech to the Human Rights Council of the United Nations. The young star of an acclaimed documentary, In My Blood It Runs, he shared his experiences about the youth justice system and his alienation from school to build support for Aboriginal-led education models that would help prevent youth offending and support their crucial connection to culture and language.

Dujuan’s speech gave voice to the young Aboriginal people who are at risk or have already entered the youth justice system. It highlighted that somewhere along the way we have forgotten the promise we made to our children that we would protect them and put their best interests at the forefront of everything we do.

As we mark the 30th anniversary of the UNCRC, I call on the government to remember the promise we made 30 years ago and raise the minimum age of criminal responsibility to 14 years of age so we stop ‘punishing’ young children when their troubled behaviour clearly tells us what they need most is support, nurture and care.