Written by Shona Reid

Today we commemorate an event very close to my heart, National Sorry Day.

As an Eastern Arrernte woman, as a mother, and as Guardian for Children and Young People, it means a lot to have the opportunity to share my reflections on the origins of this day and how our nation can learn from the past, to create better futures for First Nations children and young people.

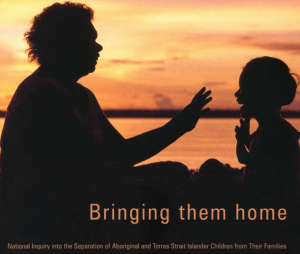

Today is the 26th anniversary of the day the Bringing Them Home Report was tabled in Federal Parliament. On 26 May 1997, this report exposed the extent to which past policies and practices were used to forcibly remove First Nations children and young people from their families and communities. It laid bare the incomprehensible harm caused not only to the individuals directly involved, but generations upon generations of children that followed.

This day asks us, as a community, to acknowledge the strength of Stolen Generations Survivors and reflect on how we can all play a part in the healing process – for not only First Nations Peoples, but our collective nation. While this date carries great significance for Stolen Generations and other First Nations peoples, it is also acknowledged and commemorated by Australians right around the country.

As with many First Nations people, my family too was impacted by the forced removals and race‑based child protection policies that have caused so much pain, and many lost family members; some of whom we are still finding today. I know too well that the harm caused by the Stolen Generations cannot be undone, and I see the consequences of this every day in my role as the Guardian.

This day gives me cause to reflect on the reasons I decided to take on this role, which have largely been shaped by my family’s experiences being caught up in the horrors of forced removals. My family’s history, and legacy, drives my desire to be part of the solution and the healing of generations both before and after me.

What I see in this role, is that so many aspects of the state of play from 26 years ago still remain an unacceptable reality today. In 2023, First Nations children in South Australia remain more likely than any other children to be removed from their families – the statistics tell us that Aboriginal children are 12.7 times more likely than non‑Aboriginal children to come into care. If that doesn’t scare you, let me share that, last year, the number of Aboriginal children and young people who were in residential care grew at more than twice the rate of non-Aboriginal children and young people.

This is why we must remain vigilant. Offences of the past, regardless of the intent, have real impacts on real people. The effects don’t just lay in the pages of history, they are lived out every day in our community.

My role as Guardian is to keep an ever-watchful eye on child protection policy and practice. I see my role as an opportunity not to fix ‘broken’ systems… but, rather, to build responses around those in need, and a system that is fit-for-purpose.

The Bringing Them Home Report highlighted for me that the foundation of past policies, practices and political agendas saw Aboriginality and Culture as a risk factor, and something that needed to be taken away from First Nations children. We know that this is a falsity and in fact Aboriginality and Culture are protective factors for children and young people, that help First Nations children to flourish and thrive. I see changes in the child protection, health, education and political arenas, where this is now acknowledged. But, the movement and practice changes are frustratingly slow. We need to hurry up.

Healing goes beyond regret and words; we need to make the system work for and with First Nations children and young people and their families.