By Shona Reid

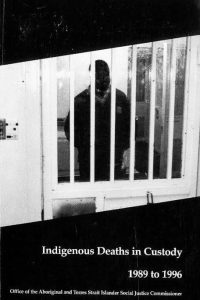

The 15 April 2023 marked the 32nd Anniversary of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody. A death in custody is the most tragic potential culmination of mistreatment or neglect in systems designed to ‘rehabilitate and punish’ alleged or sentenced offenders. We have seen too many people die while detained around Australia, resulting in families grieving, unanswered questions, and surviving detainees being affected in many harmful ways – a factor depressingly and frequently illustrated for the youth justice sector.

Concerned about ongoing deaths in custody, myself, along with other members of the Australian National Preventive Mechanism (NPM) Network, wrote a joint submission to the United Nations special review into deaths in custody.

The NPM network is an Australia-wide body made up of people responsible for implementing the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture, and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (OPCAT), an international agreement to prevent abuses of the rights of people in custody, including children and young people. As a network, we comment on policy relating to the prevention of torture and other forms of mistreatment of people deprived of their liberty.

In our submission, we outlined our concerns and made several recommendations, most specifically highlighting the importance of properly establishing and resourcing NPMs to, among other things, help identify and address poor systemic practices that might ultimately lead to deaths in custody. While OPCAT officially began in January, as NPMs, we still await the necessary resources and arrangement for functional and operational independence to fulfil the Optional Protocol’s preventive mandate.

Our submission urged the United Nations to consider how things are going with respect to implementing the recommendations of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody. We said that investigations should be both independent and culturally appropriate for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who, as we all know, are grossly over-represented across the custodial spectrum and subject to a complex array of complicating social disadvantages.

You can read the joint submission here.

Internationally sanctioned human rights set minimum standards for how people, including children and young people, should be treated while in custody. They provide the basis for holding governments and administrators accountable for protection of these fundamental rights. It is hoped that, in 2023, governments will finally put the essential resourced NPM processes in place to implement the preventive agenda in collaboration with broader civil society interests.